Copyright 2020 - 2021 irantour.tours all right reserved

Designed by Behsazanhost

Bas-reliefs of the Chogan Gorge

Bas-reliefs of the Chogan Gorge

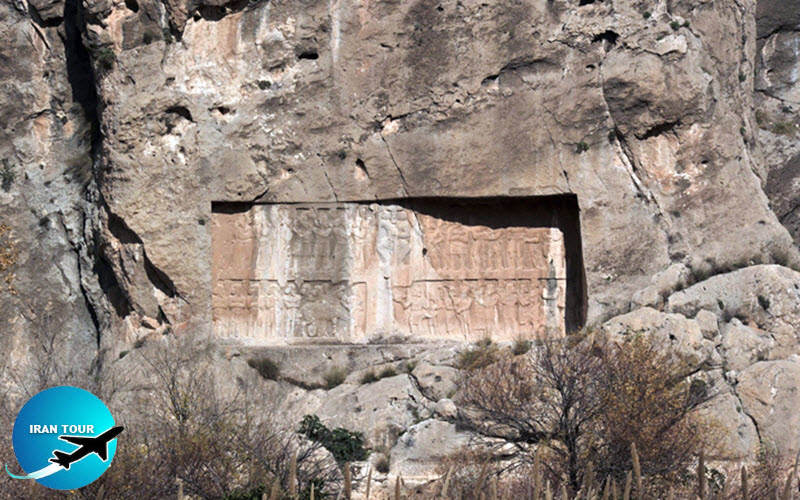

On the formerly main approach to the town, lies a scenic gorge that for centuries has been known as the Chogan (Polo) Gorge. It is called so in memory of the polo contests allegedly held here during the Sasanid period. Although this sport of Iranian origin is today unfortunately neglected, it was one of the favorite pastimes of the Iranian elite from ancient times until at least the 17th century. The gorge is crossed by the fast-flowing Shapur River, which brings water from numerous mountain springs, among them the famous Sasan Spring. The road whose entrance was initially on the highway leading into the town, but which today is inside Bishapur, goes along the feet of the mountains looming on either side of the pass Aside from its natural splendors this is the most outstanding attribute consisting of the bas-reliefs engraved on the rocky slopes. These bas-reliefs, which commemorate the military operations of the Sasanid emperors, primarily those of Shapur I, were incised to prepare the visitors for the magnificence of the town and to acquaint them with the achievements of its founder. They are sculptural victory celebrations, fashioned much in the same spirit as Roman triumphal arches.

All of the bas-reliefs have been badly damaged, but in this instance more by the forces of nature rather than by hostile hands, as in the case of Naqsh-e Rostam or Naqsh-e Rajab. Even so, they preserve their importance as some of the most significant remains of Sasanid art and exhibit the distinctive features of Sasanid rock carvings - the frontality of human and animal figures; the painstaking depiction of details of dress, ornament, and ethnic characteristics; and the rendering of

minor figures, particularly those of defeated enemies on a smaller scale than the victorious monarch so as to signify their lower, abject status.

|

-Investiture of Shapur I

Most of this carving has been completely eroded so it took great effort in order to figure out what is depicted here. The relief seems to be a combination of two subjects: the investiture of Shapur I by Ahuramazda, with the traditional composition of two horsemen trampling down their enemies; and the victory of Shapur I over Philip the Arabian, who is shown kneeling in the front of the king. The investiture scene must have been depicted in the stylized arrangement observed in the investiture of Ardashir in Naqsh-e Rostam, and of Shapur in Naqsh-e Rajab. Ahuramazda is shown on the left, and Shapur on the right of the scene. Ahuramazda gives the wreath, a symbol of royal power, to Shapur, who stretches out his hand to take it. Because of erosion, the only clothes still discernible are the trousers of Ahuramazda and the ribbons tied to the shoes of both figures. Both the god and the king seem to have worn serrated crowns.

Both horses are opulently decked out, with a caparison, adorned with metal disks and giant wool tassels. These tassels were perhaps more than a merely decorative feature and may have served as troop insignia, colored differently for various groups. Their size may also have been a feature used in identifying the rider, perhaps indicating his rank. This was essential because Sasanid troops consisted mainly of cavalry, which had to swerve, turn and respond en masse, and an elaborate signaling system was crucial. In the carving, both horses trample the prostrate figures under their feet. Beneath the hooves of Ahuramazda's horse lies Ahriman, a symbol of evil. His figure is badly eroded, and not many details can be observed. Beneath the hooves of Shapur's horse lies the figure of Gordian III. Although this emperor was killed by his own soldiers during the campaign against Shapur's army, and the Persian monarch had played no role in these events, still in the representations of the Iranian king, Gordian almost never fails to appear as a figure prostrated under the hooves of Shapur's horse. Here Gordian is shown lying on his stomach, with his head resting on his bent right hand.

|

The typical investiture scene is completed by a kneeling figure of Philip the Arabian. He is shown with his knees on the ground and his hands stretched toward Shapur in entreaty. His left-hand touches the leg of Shapur's horse. He wears a knee-length robe and a cape fastened by a round pin. Compared to the other representations of Philip in Iranian bas-reliefs, this is the most dramatically impressive scene. Here the artist managed to express the feelings of the emperor and to draw attention to his sorrow and distress. In fact, of all the Sasanid carvings, it is only this one that indicates that the artist was aware of the emotions of the people he depicts. This, as well as other elements of the carving's artistic treatment, suggests that it may have been made with the collaboration of a Roman artist.

This carving of Bishapur is also of outstanding historical value. It is known that Shapur was crowned twice, first around 241 A.D., with the crown of his father Ardashir, who, toward the end of his life, abdicated in favor of his son and lived the life of a hermit in the Temple of Anahita at Estakhr. (Shapur is shown wearing this crown on the bas-relief in Darab, The date of Shapur's second crowning, with the famous serrated tiara which appears on every later portrait of him, is unknown, but the ceremony obviously took place after his father's death. This Bishapur carving may endeavor to show that the second crowning took place after Shapur's victory over Philip around 244. In light of the foregoing, this bas-relief combination of Shapur's coronation and his victory does not appear totally unrelated.

The size of the basrelief is about 10 m long and 5 m high.

|

-The victory of Shapur I

A little beyond the investiture scene is another bas-relief, commemorating the king's third victory over the Romans. Also, Shapur's triumph over Valerian is pictured in a bas-relief on the opposite side of the gorge, and in Naqsh-e Rostam as well. The three carvings vary in terms of their participants and the craftsmen's attitude toward them, but they all show the glorious king in the midst of his courtiers and overpowered enemies. This carving, 13.5 m wide and about 5 m high, shows an impressive number of people arranged in a central scene, with bordering frames. Altogether the relief consists of eight sections. The carving is fairly well preserved, as it has been protected by an overhanging canopy of rock.

The central scene shows Shapur I on horseback. His horse, though relatively small in comparison with its horseman, is shown in relentless detail. The magnificent horses bred for Sasanid cavalry were a commodity much in demand in China and the West. They could easily carry fully-armored men in battle, making Persian-mounted troops a superior force. The horse's decorated forelock is a feature typical of the Persian horse's embellishment. It was often ornamented with ribbons, demonstrating that ribbons were an essential decorative element for both horse and horseman. The harness is also embellished. The saddle has two crescent supports, used in place of stirrups (which had not yet been invented), but these are better observed in other Sasanid carvings.

As in the previous bas-relief, Shapur's horse tramples the figure of Gordian III. In front of the king, and stretching his hands in entreaty toward him, kneels Philip the Arabian. Slightly behind the king stands the third Roman Emperor, Valerian. His left hand is half-concealed beneath his coat, while his right hand, stretched toward the king, is hidden in the sleeve, as prescribed by Sasanid protocol. Above this group hovers a cherub with large wings. In his hands, he holds a large ribbon. Not typical of Sasanid carvings, this angel of victory is undoubtedly borrowed from Roman art. Two other figures complete the middle scene. Behind Philip stands a Persian nobleman in a tall hat and heavy necklace. He may be a military personage of high rank Another individual here is also Persian. His hat, curved forward used to have an emblem shaped like an animal, which showed that he belonged to the royal family. Interestingly, his shirt has a concave border, an element that became fashionable during the rule of Shapur II, about one hundred years later. He stands on his tiptoes, a convention which in Sasanid carvings signified walking, and seems to lead the group of people depicted in two rows behind him. He may be one of Shapur's sons.

Two engraved spaces on the left, and two on the right (these two divided into five individual subjects), frame the middle scene. Sasanid principal military men and nobles are shown on horseback to the left of the middle scene. They all point with their right index fingers, showing deference in the presence of their king. The lower row shows more highly-ranked officials, three of whom, as their headdresses testify, may be members of the royal family, and perhaps are Shapur's sons. The horsemen in the upper row have lower ranks. The upper panel contains four, and the lower panel, three Sasanid officers, while in each row another person is indicated by his horse.

|

The frames to the right show figures on foot, and carrying war trophies. The lower row has three frames; the upper two each show three men. The most important group appears in the first frame of the lower row. The object held by the first person cannot be seen, but the second and third persons have long spears in their hands.

The second frame shows three unarmed persons. The first person holds in his raised right hand a ring, probably symbolizing victory. The second person, in his left hand, holds a long, cylindrical object that seems to be a scroll; he may represent a scribe. We cannot see what the third person carries in his right hand.

Three men in the third frame are also unarmed. The first person uses both hands to hold a long, heavy object, perhaps a bundle of sacred twigs; the second carries the same object; while the third carries a huge vase. They seem to be Zoroastrian priests.

The first frame in the upper row shows three men, whose appearance suggests that they are not Iranians, and who may be the representatives of different peoples. These men are most probably Roman allies or mercenaries, who in the 3rd century comprised an essential part of the Roman army. The second frame shows Persian soldiers. The first two have their left hands on the hilt of their swords, while the left hand of the third person, hidden in his sleeve, falls at his side. The first of these three carries an object in his right hand, though we cannot distinguish what this may be. The other two men have their right hands resting on the shoulder of the person in front.

The success of this bas- relief cannot be judged (as too often has been the case) in terms of classical standards. The artists, unlike their Western counterparts, were not concerned with realism. They were adhering to a time-honored Eastern representational language of art, in which size, position, and symbols express the meaning. The disproportionately large figure of Shapur which dominates the entire scene serves to heighten the aura of power and divine glory which the artist sought to convey. In this language of symbols, it is logical that the defeated Valerian standing at his side should be reduced to less than normal proportions. These anomalies have been brought together so skillfully, however, that unless one analyses the scene critically, they can be easily ignored.

|

-Victory of Shapur I

This magnificent bas-relief, another scene representing Shapur I's victory over the Romans, was scooped out to form a concave surface that allows the portraits of more than a hundred people and sixty animals on what would have been a rather short length of cliff space if it had been handled flat. This engraving chronologically follows the second bas-relief on the opposite side of the river. The king is shown facing right, in the middle of the bas-relief. His face is badly mutilated, but his serrated crown, a tall turban, and a diadem with a crimped ribbon are still visible. The king wears the same clothes as in his portrait on the opposite side of the river and on his statue in the Shapur Cave.

The horse is much smaller than its rider and is badly eroded. Very few details of its decoration have survived, and only its beautiful forelock and plaited tail are still visible. Gordian III is shown prostrate beneath the hooves of Shapur's horse. The figure of Valerian has also been destroyed. He is shown with his left hand held by the Persian monarch. Philip the Arabian is depicted kneeling on his left knee in front of Shapur and stretching both of his hands to him in a plea. He is much smaller than the two figures standing beside him.

The first figure behind Philip is a Persian nobleman. The second person, standing behind the first and partially hidden by him, may be the prince also shown in the carving on the opposite side of the river. A cherub holding an unrolled chaplet floats in the air above Philip and two Persian noblemen. The central scene is flanked on the right and the left by two other carvings. Both of these are divided into five horizontal rows which extend beyond the central scene. The carvings on the left show high-ranking Persian officers rendering homage in the king's presence by pointing upward with the right forefinger. They may be awaiting the arrival of the long procession depicted on the right, and consisting of Roman soldiers and Persian courtiers.

The most important Persian noblemen are portrayed in the third row from the top and to the left of the middle scene. Leading them are three princes - Bahram, Shapur, and Narses - the younger brothers of Hormoz, who seem to have been shown in the middle. The high-ranking military men behind them may be the representatives of the famous seven elite families of ancient Iran. The remaining three men do not differ from the officers depicted in other rows and may belong to the same rank. The two upper rows on the left show the officers of the lowest rank in the group. They are more modestly dressed and wear simple hats. Although these figures have suffered mutilation over the years, they exhibit outstanding precision and delicacy of craftsmanship. This suggests that the figures were carved by more than one artist, and perhaps by a group working on the bas-relief.

The first and second rows on the right depict Persian attendants carrying the booty that had been seized from the Romans. All wear similar clothes, have hair similarly arranged, and no one is armored. The first and second persons in the upper row are badly eroded. The third person has his left hand hidden in his sleeve, while in his right hand he carries a vase. The fourth person holds a long object in his right hand. The sixth man has two rings and is followed by the seventh person, who carries a vessel. The last and eighth person in the row also has two rings in his hands.

|

The first person in the second row from above carries a ring; he may have once had another ring in his other hand, but this has disappeared (these are easy to see in old engravings of the scene, but are hardly distinguishable now). He seems to have been the head of the courtiers. The object which he had in his left hand, has disappeared. The second Persian holds a large, fluted vase above his head. The third and fifth persons carry a wooden stick with a burden attached to it. The fourth man behind these two carries a fluted vase. The sixth man carries a heavy sack, holding it with both hands. The seventh person leads two animals, perhaps lynxes, while the eighth also holds a large, fluted vessel above his head.

The third row starts with a figure holding a round object. He is partially concealed behind another man, who holds the reins of a horse. This horse is decorated differently from Persian steeds. Its very long tail is not plaited but tied with knots. Behind the horse stand two Persian figures, who may have escorted the procession. Only the head of the first has been preserved, but a large vessel can be seen in the hands of the second one. Following them is an elephant driven by its mahout. The animal is so childishly portrayed as to make it obvious that the artist had little or no knowledge of what the original really looked like. This impression is enhanced by the elephant's foreleg, which is bent as if the animal were walking while standing still.

In the rear row appear six men with long hair. Their clothes, or maybe a large piece of cloth, form a remarkable backdrop for the figures in the front row. The lower row shows a Roman leaning against a cane and holding a vessel in his right hand. Behind him is another Roman carrying a vase. The third person is also Roman; in his right hand, he holds a mace. These men are followed by a Roman chariot pulled by two horses. Another Roman is seen behind the horses. The Roman holds an oval object, perhaps a vessel, in his hand. Behind the chariot are two other Romans. Their figures are badly mutilated, but it is obvious that they both carry heavy sacks in their hands. The bottom row is almost entirely ruined, and it is impossible to distinguish its details. Despite such a vast scope, and the impressive number of participants, all the people in the side frames were carved only to highlight the middle scene and to emphasize its importance. This bas-relief was most probably carved by Iranian artists.

|

-Victory of Bahram II

This carving shows the victory of Bahram II, over an alien tribe, perhaps the Arabs. A water canal scored a deep groove in the rock, cutting the bas-relief in two. In 1877, when this carving was discovered by archaeologists, it was already badly damaged. In 1937, archaeologists succeeded in diverting the watercourse, and thus saved the relief from further injury.

Bahram II on horseback is on the left side of the carving. He wears a distinctive crown with an eagle's wings, a symbol of Bahram, patron of victory. The monarch holds three arrows in his left hand, and there is a quiver fastened to his belt. The three arrows may have had a symbolic meaning; it is possible that they represented the vigor and strength of the sovereign. (It is known that rebellious Scythian chiefs once sent three arrows to Darius the Great as an arrogant reply to his order of surrender.)

In front of the king stands a Persian officer, perhaps a commander of the military operation. Behind him in two rows are depicted the representatives of the conquered lands. Three men in the front row wear full-length robes, and keffiyeh, or kerchiefs covering their hair and held in place by circlets - the clothes still worn by desert-dwelling Arabs. They bring two horses, which are carved behind them. In the back row, another three men are depicted, these bring two camels with them.

|

Investiture of Bahram I

This carving commemorates the inauguration of Bahram I. He is shown on horseback at the right of the scene. The king's posture demonstrates his power and strength. However, his potential as a ruler was never completely realized, since he ruled for only three years. The king wears a crown with ray-like ends, a symbol of Mithra, and a tall turban. He is armed with a long sword and has his left hand resting on its hilt. His elegant horse is consummately presented. Many consider that the art of animal portraiture practiced since at least the Achaemenid period found its culmination in this depiction. The figure on the left is a representation of Ahuramazda, who grants the royal wreath to the king. Shown on horseback, the god has a serrated crown similar to that of Shapur I.

The inscription in Sasanid Pahlavi to the right of the relief has badly mutilated. It once contained the names of Bahram I, his father Shapur I, and his grandfather Ardashir Babakan, together with praise of Ahuramazda. Later, however, the name of Bahram was replaced with the name of Narses, Bahram's brother, perhaps in order to justify his usurpation of the throne. The inscription runs: "This is Narses, the Ahuramazda worshipper, King of Iran and non-Iran, whose face resembles that of God. He is the son of Shapur, the Ahuramazda worshipper, the King of Iran and nonIran, who has a divine face and was a descendent of Ardashir, the King of Kings. At Narses's order, a prostrated figure was added under the hooves of the royal horse. Some belief it to represent Bahram III.

|

The victory of Shapur II

This bas-relief is carved on the last usable spot of the cliff-face. Dating from the 4th century, it is the latest among the engravings of the Chogan Gorge, and belongs to the rule of Shapur II Zulaktaf (The Broad-Shouldered). This vast relief was never completed, while parts of it have been mutilated over the course of time. The carving occupies a rectangle 10.5 m long and about 5 m high. It is divided into four parts. In the center of the upper register is a portrait of the king sitting with his knees wide apart. His left-hand rests on the hilt of a longsword, the blade of which is shown between his strong calves, while in his right hand he has a tall lance or gigantic battle-ax. The king, unlike the other kings in the gorge, is shown directly facing the spectator, and his hair is bushed out on either side of his stern face. The figure of the king has not been entirely completed, and his head, crown, and frontlet are only sketchily done. Two rows of figures have been carved on either side of the king. The upper row to the right of the king shows Persian military men bringing vanquished enemies into the presence of the king. The first person in the row may be a commander who won a victory in battle. He wears a knee-length robe with the concave hemline prescribed by the fashion of this time, and a hat curved to the front. He has a sword in his left hand, and may once have paid homage with his right hand; however, a fissure of the cliff has destroyed this.

The second person, partially hidden behind the third man, is a standard-bearer. His large banner flies above the heads of the three people in the row. The third person is a high-ranking officer. His hands are crossed on his chest, and both hands are hidden in his sleeves. The fourth person is a captive with both his hands tied. He is dragged by the fifth man, whose beard, tall hat, and the sword at his waist indicate that he is a Persian military man. The sixth person is almost completely concealed behind the fifth and seventh persons. We can see only his face with a thick beard. He too may be a Persian officer.

The seventh person is also a prisoner with his hands tied behind his back. He looks back at the person who leads him. He seems to be wearing, like the previous prisoner, only a loincloth. The eighth person is similar to the third and fifth. He is a Persian officer leading a prisoner. The ninth person has his hands hidden in his sleeves and crossed on his chest. He has no weapons. In the back row, behind the eighth and ninth persons, the heads of three Persians can be seen as their bodies are hidden behind the people in the front row. The second of them brandishes his sword in the air.

|

The upper row to the left of the king depicts another group of Persian officers and court dignitaries. Most of them show a customary gesture of respect with the bent forefinger of their right hand. The back row shows four officers with similar posture. The row to the lower right of the middle scene portrays a gruesome procession of Persian military men and their entourage bringing prisoners and the spoils of war into the presence of the king. The first individual, who may be a chief attendant, holds the severed heads of enemies in his hands. He is followed by a child, definitely related to the slaughtered man. The child clings to the robe of the man who carries the heads. Another severed head, that of a younger man, is shown behind the child. It still wears a hat with a bent peak. Its owner may have been a member of the royal family, perhaps another relative of the victims. This head is carried by a man who is hidden behind the fourth and fifth men in the front row. The fourth person is a prisoner in a hat similar to that of the younger decapitated man. He is led by the fifth person, obviously a Persian officer. The seventh person also carries a severed head in his hand. The eighth person, perhaps a priest, has an object which looks like a scroll. The head of the ninth person is seen in the back row between the seventh and the eighth men. The tenth person, standing behind the eighth man, holds an object that cannot be made out. Behind him is shown an elephant led by a rider. As in the carving of Shapur I, the animal is unrealistically proportioned. Of the twelfth person, standing in the rear row, only the upper front of the body can be seen. He holds a sword or a dagger in his hand. The thirteenth person, partially hidden by the diminutive elephant, carries a vase. The fourteenth person holds what seems to be a bundle of sacred twigs, and maybe a priest.

|

The lower row to the left of the middle scene shows the Persian court officials and military commanders. The first of them leads the king's saddled warhorse, decorated with huge tassels. All the men here look very much the same; all have hands hidden in the sleeves and crossed on the chest. This carving exhibits a considerable decline in the art of carving, as compared to earlier examples. The incompetence of the artist is evident, and the shallowness of the lines makes the carving look more like a painting than an actual bas-relief. Although the inferiority of the work is obvious in the technique, it is perhaps even more marked in the content. No such sordid picture was executed in earlier examples. Severed heads, a child anguished by the slaughter of his family, and the shah's hauteur displayed against this dreadful backdrop - all are sufficient evidence for seeing in this engraving a portrait of Shapur II, infamous for his cruelty. Nonetheless, the bas-relief is essential in revealing the conditions existing in the 4th-century Persian court, as well as the important victory achieved by Shapur II towards the end of his reign in the far-eastern regions of his country.

|

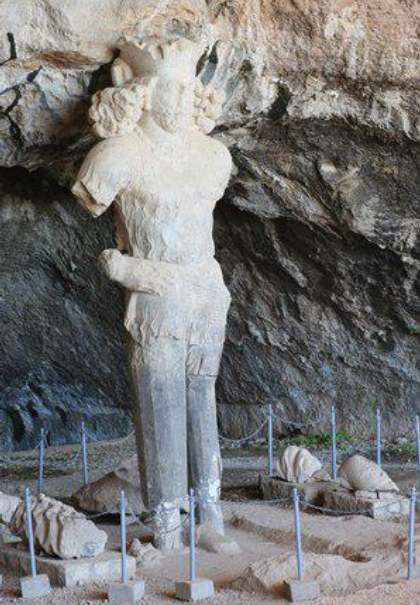

-Shapur Cave and Statue

Mt. Shapur is located about 25 km northwest of Kazerun. It reaches 1,556 m in height. The Shapur River runs along its south slope, where the famous cave is located about two-thirds of the way up the mountain. To reach the cave, one has to go from Bishapur through the Chogan Gorge along the right bank of the river. After about 4 km, the river must be crossed by a ford, so as to reach a small hamlet at the foot of the mountain. A former army trail, which winds up and around the cliff, is negotiable by a four-wheel-drive vehicle as far as about 400-500 m above ground level. The remaining 300-400 m must be traversed on foot to reach a staircase of more than two hundred steps, which ascend to the cave entrance. Although this way is simpler and faster than the direct assault, it is still recommended only for athletic, healthy people in good physical shape. Tourists may hire a local guide in the village for a small fee. There is no water along the way, and since the water in the village tastes very bad, it is advisable to bring a supply of bottled water. The climb takes an average of an hour and a half. In summer it is very difficult because the heat is scorching during the daytime.

Because the cave is relatively large and has many slippery pits, chasms, and side passageways, it has never been explored completely. What is known is that it extends about 1 km into the earth and that the floor level of the mouth of the cave is higher than that farther in. Moreover, it is very dark inside, so one should never try to explore the cave alone or without proper authorization. People are known to have been lost in it.

|

The majestic statue of Shapur I stands at the I entrance to the cave. It is carved from an accreted stalactite and stalagmite in situ so that the king's crown sits against the ceiling and his feet take a firm stand on a pedestal shaped from the solid mother-rock. Completed about 270 A.D., the huge statue reaches 7 m in height and weighs more than 30,000 kg. The heavy statue collapsed under its own weight, and in falling, broke its arms and legs. Fortunately, the head, attached to the cave ceiling and held up from behind by the mass of hair and crimped ribbons, survived. The date when the statue fell down is anyone's guess; some think it may have been around 1400 years ago, and early Islamic geographers already refer to it as a fallen idol. The sculpture was repaired and returned to the vertical position only in 1958, this time with its newly-added, makeshift legs of reinforced concrete. The disintegrated sections of legs and arms have been placed beside the figure.

In its general style, the great figure of Shapur follows closely that of this king on the rock reliefs. However, as a natural result of the limitations imposed on the sculptor by the circumstances here, the sculpture is stiff and hieratic. Still, it has been executed with great competence to fit into the prescribed space, and there is elegance in the treatment of the great torso and a commanding presence in the strong face.

It may seem strange that such a magnificent statue was placed in such a remote site. The only reasonable answer is that this site was chosen by the king to be his final resting place. Putting up a statue at a gravesite was by no means a common practice, and may even have been contrary to contemporary religious edicts. However, Shapur had enough power to oppose the clerics. The idea of marking his grave with a sculpture may have come from things he observed in Roman territories. So far, there has been no grave or ossuary found in the cave, but locals claim that their ancestors did see an ossuary filled with what could have been Shapur's bones. The fact that Shapur died in Bishapur, and must have been buried somewhere in its vicinity gives further credence to this theory. Some of the walls on either side of the cave have had flat panels carved into them; on these, inscriptions or figures were to be engraved. However, time may have run out before the king could complete his burial place, and the panels remained blank.

- Details

- Category: Museums of Shiraz