Copyright 2020 - 2021 irantour.tours all right reserved

Designed by Behsazanhost

Persepolis The Treasury

Treasury

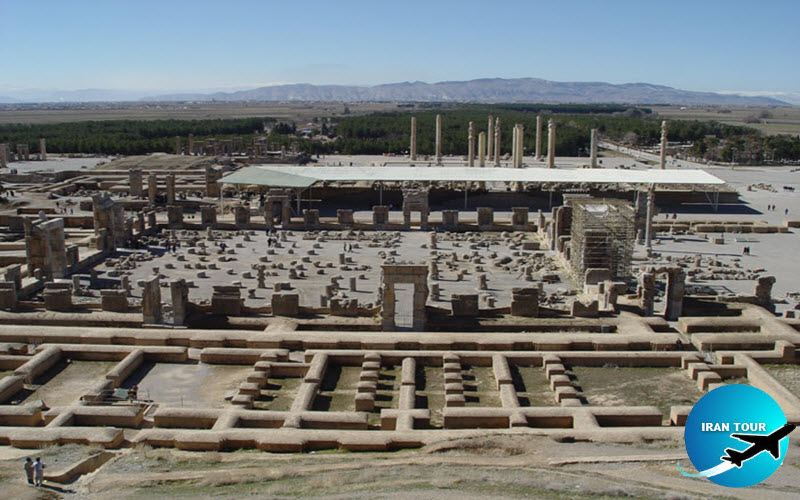

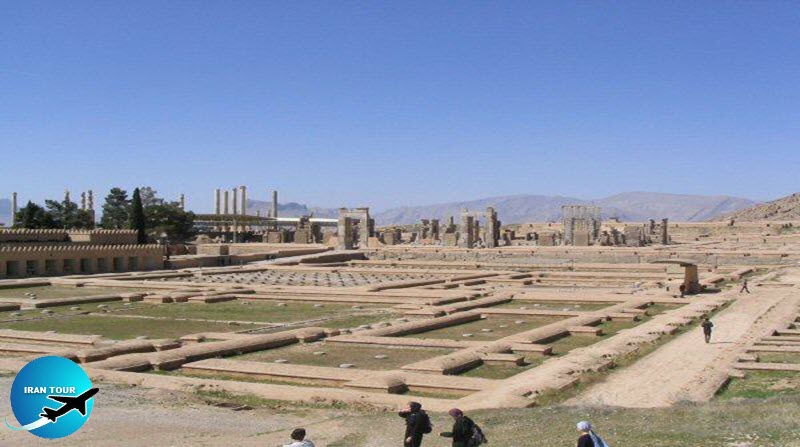

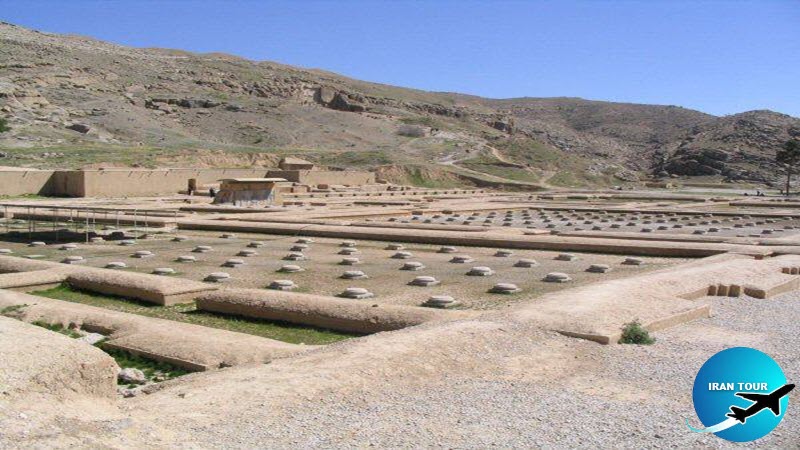

Unquestionably the earliest structure in Persepolis, the Treasury was constructed in several stages. It was conceived by Darius, expanded later during his reign, and further enlarged under Xerxes. Originally, this huge building was enclosed by a high, mud-brick wall, and had an entrance on its west side. The entrance opened toward a line of small guardhouses, which were followed by three halls with four columns, and one room with two columns. Four large halls, two on either side of a long passageway, occupied the center of the building. The two halls on the north had thirty-six columns each, while each of the halls on the south was supported by twenty-four columns. To the east was a large, open, inner courtyard, surrounded on each side by columned porticos and additional chambers. Such was the layout of the Treasury in 507 B.C.

|

However, still, under the rule of Darius, the Treasury proved too small. It was therefore expanded toward the north by adding two halls, an immense hall with ninety-nine columns, an open courtyard bordered by columned porticos, and a number of auxiliary chambers. This expansion enlarged the Treasury to about twice its initial size. Another entrance was added to the north wall of the building. During Xerxes's reign, part of the western section of the Treasury was demolished to make room for the Harem. However, the building was again expanded toward the north, and a huge hall with a hundred columns and several guardrooms was constructed there. Perhaps these amendments were undertaken following Darius's plan since Xerxes claims in his inscription that he preserved and added to whatever his father had built. This "third" version of the Treasury has been construed from the remains of the mud-brick walls and stone bases of the columns, which have been excavated by archaeologists. All the columns in the Treasury had slender wooden shafts sheathed in a layer of painted plaster and set on round or rectangular stone bases. Some of the stone elements bear a variety of masons' marks. There is no evidence of windows, and the enclosed areas may have been very dark, except for the courts, which were left open to the sky.

|

Thus, the courts may be the most favorable place for carrying out the administrative tasks of record-keeping and making inventories. In general, the combination of very large halls, smaller chambers, and porticos seems poorly suited for the storage of items in an orderly fashion, or for their easy retrieval. The excavation of the building and the study of its artifacts have revealed that the Treasury was an imperial museum with items including gifts from subject lands, objects assembled from conquered cities, and other valuable goods. The artifacts recovered from the Treasury fall into a number of categories: tablets concerned with payments to workers, clay labels stamped with seal impressions, cylinder and stamp seals, ritual objects, coins, sculpture, jewelry and ornaments, votive objects, weapons, tools, and utensils. Most of this was smashed to bits when the Macedonian soldiers looted and wantonly destroyed the Treasury. Historians report that thousands of camels and mules were brought from Susa to let Alexander remove the valuables, of which the silver alone constituted 4,400 kg.

|

Among the pieces left behind by the looters were the clay tablets in Elamite. Their discovery has shed some light on the administrative organization of the construction work in Persepolis. The tablets give exact details of wages in cash and in-kind, paid to the men, women, and children who worked in Persepolis, proving that This gigantic undertaking was constructed by none enslaved, paid labor, in contrast to contemporary monumental buildings in other countries where slave labor was the rule.

Among the other masterpieces of the Treasury were two identical orthostats, showing scenes of royal audiences, which were transferred here from the Apadana stairs. The better preserved of the two, now in the National Museum in Tehran, has the king facing right. The other, which remains in Persepolis, is identical, except that the scene is reversed, with the king facing left. In the Treasury relief, Xerxes is shown seated on a high-backed chair, his feet planted firmly on a footstool. In his right hand, he holds a tall scepter, and in his left, a lotus flower.

|

Behind the king, on the same low platform that supports the throne, stands Darius, Xerxes's eldest son, and crown prince, who was murdered before he could take the throne. His clothes are identical to those of his father; they include a full-length, longsleeved, pleated Persian robe and a tall, cylindrical hat. He has a square-cut beard, which reaches to the middle of his chest and is groomed in alternating rows of waves and curls - a hallmark of royalty. In his left hand, he holds the bud of a lotus, a flower associated with royal power, while with his right hand he makes a gesture of salutation to the king. Behind the prince stands a royal chamberlain, wearing a Persian robe and a turban wrapped so as to cover his chin. His right-hand holds a piece of cloth, possibly a folded towel. His left-hand lies with fingers extended upon the wrist of his right hand, a gesture long used to suggest absolute obedience in the courts of the Middle East. The chamberlain is followed by an attendant in Median clothes; he carries a ceremonial royal battle-ax and a bow slung over his shoulder. The chamberlain and the weapon bearer, who are aligned on the ground behind the prince, were probably meant to stand on the enthroned king's left side. Two soldiers end the procession.

|

In front of Xerxes are depicted two incense burners. These separate the king from a man dressed in a Median costume and bowing in deference to the king. He holds a short staff in his left hand and keeps his right hand in front of his mouth, perhaps to prevent his breath from defiling the monarch. His identity has been suggested as that of the commander of the royal bodyguards, who was also a principal organizer of the procession of the people of the empire. The empty space above the two censers, separating the king from the man received in the audience, dramatizes the distance between the two figures. Yet the man has the same strong features as the king and as all other persons in the relief. He is followed by two other soldiers. The scene took place under a baldachin, which is decorated with a frieze of roaring lions flanking a winged circle and bands of twelve-petal rosettes. Of this baldachin, only the poles and some of the tassels remain; the canopy itself was on a higher register, whose blocks have not survived.

- Details

- Category: Museums of Shiraz