Copyright 2020 - 2021 irantour.tours all right reserved

Designed by Behsazanhost

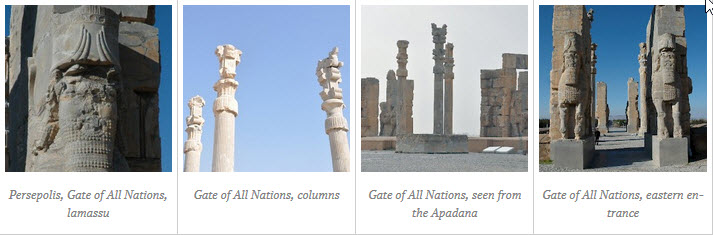

Persepolis Gate of All Lands (Nations)

Gate of All Lands (Nations)

The first palace of the complex is known as the Gate of All Lands. Built during Xerxes's reign, it served as a waiting room for the people expecting to be summoned before the king. The palace consisted of a square hall and three massive portals, overlooking its east, south, and west sides. The hall measured 612.5 sq. m and was about 17 m high, with its ceiling supported by four stone columns. Of these, two have survived, and the third was reassembled from the remaining fragments. (This is now the most nearly complete column in the complex.) The walls of the palace were made of mud-brick and were remarkably thick, as can be seen from the low mounds now marking their bases. One can also see how the outside of the stone doorways was irregularly hollowed out to allow for proper bonding between the door and the adorning wall The central ball seas were lined with stone benches where guests could sit waiting their turn for an audience with the king.

|

The interior of the hall was adorned with brightly-colored tiles laid in patterns of twelve-petaled rosettes and rows of date palms: pieces of the tilework are now assembled in the eastern gallery of the restored Harem. The west and east portals measure 10 m high and almost 4 m wide and are adorned with magnificent guardian colossi. The south portal lacks any decoration but is wider and higher The west portal, marked by two large bulls whose forequarters project forward from massive piles of masonry overlooks the plain and serves as an entrance to the palace. The head of the monster to the right of the spectator has completely disappeared, and the neck of that

on the left survives, but the whole front of its head has been hacked off beyond all possibility of recognition. Around its neck hangs a collar of flowers. On the chest and between the forelegs of both beasts, as also on their shoulders, ribs, and flanks, are masses of hair in tight, round curls.

| From an ancient inscription in the gate, known as XPa, we learn that the name of this monument was "Gate of All Nations". The text is trilingual: to the left and right of the Old Persian inscription are Babylonian and Elamite translations. A great god is Ahuramazda, who created this earth, who created heaven, who created man, who created happiness for man, who made Xerxes king, one king of many kings, commander of many commanders. I am Xerxes, the great king, the king of kings, the king of all countries and many men, the king in this great earth far and wide, the son of Darius, an Achaemenid. King Xerxes says: by the favor of Ahuramazda this Gate of All Nations I built. Much else that is beautiful was built in this Persepolis (Pârsâ), which I built and my father built. Whatever has been built and seems beautiful - all that we built in the favor of Ahuramazda. King Xerxes says: may Ahuramazda preserve me, my kingdom, what has been built by me, and what has been built by my father. That, indeed, may Ahuramazda preserve. |

|

The east portal bears a design of two sphinxes, with bodies of bulls, eagle wings, and bearded human heads. Although resembling lamassu, the Assyrian guardian figures, they bear some differences from their Assyrian prototypes. They look onto the terrace instead of striving to meet the enemy arriving from outside, as they do in the Assyrian emplacement. They are four-legged instead of five-legged, and their wings sweep upward into the air instead of being laid back, as in the case of the Assyrian colossi. Unfortunately, the heads of the statues were deliberately damaged by Muslim iconoclasts. Yet, the great beards still lie intact upon the stalwart chests, earrings hang from the ears, bunches of hair heavily frame the vanished faces, and the heads are crowned by lofty tiaras, which terminate at the summit in a fringe or coronet of feathers, while circular bands, curling upwards in the shape of horns, adorn the front.

|

The east gate opened onto the Army Street, which led to the Hall of a Hundred Columns, and which was lined by guards on ceremonial occasions. This street was walled off with a high, double retaining wall of mud-brick, which obstructed any view of the palaces; today, only the lower remnants of this wall have been preserved. The south portal led to a small forecourt of the Apadana. Because the south portal provided the nearest approach to the Apadana, this may have been reserved for Persian and Median dignitaries. It was completely built of stone, but only the doorjambs and patches of the paved floor have survived. The double-winged gate, opening inwards, was wooden, but was plated with metal panels adorned with carved animal figures. The sockets, each shaped like a large bowl with a border of twelve-petaled rosettes can still be seen on the floor here. Usually, the gate was closed, and visitors used a small wicket gate for going in and out. From the darkness of the gate chamber, the sight of the Apadana, with its splendid | socle reliefs topped by the lofty portico's black columns against the light background of the walls, must have been overwhelming. Everything in Persepolis was supposed to astonish the visitor and prepare him for the most striking sight, that of the King of Kings", the incarnation of the Divine on Earth.

The east and west doorjambs feature cuneiform inscriptions by Xerxes in Old Persian, Elamite, and Babylonian. These beautiful inscriptions contrast markedly with the graffiti left by many visitors to the site, some of whom are quite famous, such as Carsten Niebuhr, 1765 (German traveler who was the sole survivor of the first scientific expedition to Arabia), Captain John Malcolm, 1800 and 1810 (British Governor of Bombay and the historian of Iran), James Morier, 1810 (English diplomat and writer of The Adventures of Hajji Baba of Ispahan), Comte Joseph-Arthur de Gobineau, 1840 (French diplomat, writer, ethnologist, and social thinker), and Sir Henry Morton Stanley, 1 1870 (British American explorer of South Africa, who came to Iran as a correspondent for New York Herald).

- Details

- Category: Museums of Shiraz