Copyright 2020 - 2021 irantour.tours all right reserved

Designed by Behsazanhost

Mashhad-e Ardehal Kashan

Mashhad-e Ardehal

Located 49 km to the west of Kashan, Mashhad-e Ardehal is located in an arid valley, stretching from northwest to southeast and encircled by a row of mountains and hills of varying height. The village has mild summers and very cold winters. Most of its residents are engaged in agriculture and gardening; the main handicraft is carpet. On the road to Mashad-e Ardehal, the tourists may choose to stop in the village of Joshaqan Astark to visit the Safavid mausoleum of Imamzadeh Mohammad Owsat. They can also visit the village of Naraq and its famous mausoleum of Baba Afzal, a notable 15th-century Sufi.

|

Ardehal has the same Pahlavi root as Ardestan and means "pure, sacred hills". The sanctity of the site has remained during the Islamic period and reached its apogee when Sultan Ali, son of Imam Mohammad Baqer, was martyred and buried here. Since then, the village became known as Mashhad-e Ardehal, Mashhad meaning "the place of martyrdom". It is believed that Sultan Ali's wife and several other notable people of his time were buried beside the grave of the reverend saint.

|

Mausoleum of Sultan Ali ibn Mohammad

The original mausoleum used to be a plain Chahar Taq built as early as the Buyid period. Under the Seljuk reign, in 1141, the mausoleum was expanded with the financial assistance of Majd al-Din Obeidollah Kashani. At this time, the complex included, in addition to the domed chamber of the mausoleum, a court with pilgrims lodgings, a bazaar, a caravanserai, and a bathhouse - all surrounded by a splendid garden. In succeeding years, the complex was constantly rebuilt, refurbished, and expanded. In the 15th century, minarets and a drum-house were added. The interior was decorated with paintings, while the dome's exterior was covered with tiles. However, the most important renovations took place during the Safavid period. Under Shah Sultan Hossein Safavid, Timurid mosaics of the dome were replaced with gilded Safavid tiles featuring floral designs and arabesques. During the Qajar period, extensive reconstruction was carried out on the site, much of which has changed the original structure irreversibly. The constructions of the modern period have finally altered the building's original layout.

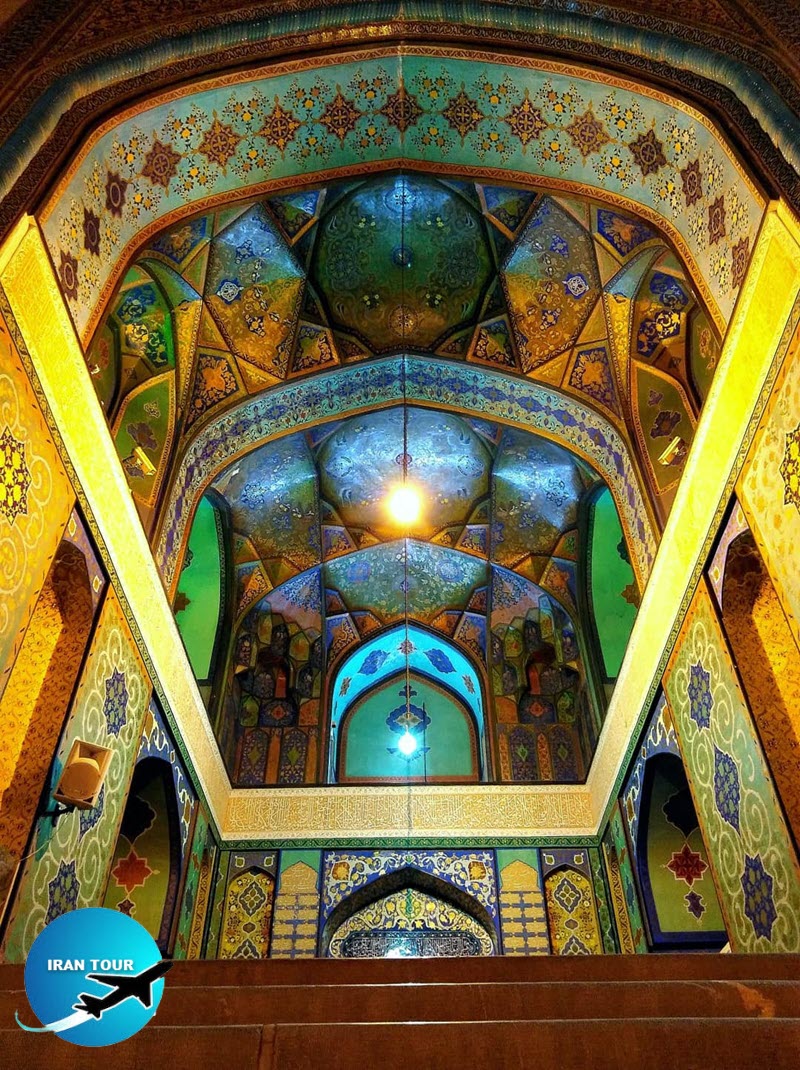

In its current state, the mausoleum features a Seljuk dome decorated with Safavid-period tilework and paintings; three high eivans; several minarets dating from the Qajar period; courtyards with pilgrims' lodgings; and many additional structures. The interior decorations include paintings, mirror-work, and tiles, dating mainly from the 18-19th century. The mausoleum used to have Seljuk tiles - the oldest found in Iran - but they were looted in the early 20th century. The eivan and the court on the eastern side of the mausoleum were built by Mashallah Khan, son of Naeb Hossein Kashi in 1917, in place of a courtyard and a Madreseh that he had ruined. They are famous as the Sardar (Commander's) eivan and court. Two tall, hollow minarets and three shorter, solid minarets soar above the Sardar court. The walls of the eivan, dominated by these minarets, are decorated with paintings portraying the religious figures of the early Islamic period. The courtyard in front of the eivan has twelve pilgrims chambers along with two of its opposite sides. It is also sometimes called Finiha (Fin residents') court, as they gather here during the Carpet-Washing ceremony.

|

The south eivan is the largest and is reached by a flight of ten steps. It was added during the Safavid period and in the past was a favorite place for dervishes' gatherings. It is sometimes called the Safa eivan, after the sect to which the dervishes belonged. This eivan features the most exquisite decorations, including lavish Safavid paintings, Moqarnas, and a plaster inscription running along the eivan's entire perimeter. The court in front of the eivan was laid out during the Timurid period, and extended by Safavids and Qajars. It is often called Papak, allegedly after one of Sultan Ali's mortal enemies. People believe that by trampling the court, they curse the betrayer.

There is also another eivan, at the top of a flight of eighteen steps. It is plainly whitewashed and, except for some Moqarnas, is notable only for a royal order of Shahrokh Mirza, indicative of tax exemptions granted to the residents of the village in the 15th century. Inside, the mausoleum has two prayer halls, one of which is famed as Cheraq-Khaneh (“Lantern House”), because pilgrims lit candles there. Until recently, the grave of Sultan Ali was covered by two wooden fretted sarcophagi, the larger placed on top of the smaller. An engraved inscription ascribed them to 1594. At present, they have been replaced by a damascened casket, made by Esfahan masters. Numerous gravestones are scattered around the mausoleum, one of which, in the eastern court of the shrine, belongs to Sohrab Sepehri.

|

Qali-Shuyan (CarpetWashing) Ceremony

This ceremony, unique to Mashhad-e Ardehal, takes place every year on the second Friday of the Iranian month of Mehr. However, if the ceremony coincides with another religious holiday or a mourning day, it is held the week before or is put off until the week after. As a rule, it should be taken between the 1st and the 17th of Mehr. Starting the week before the ceremony, pilgrims gather at the site. The annual bazaar, which dates back several hundred years, is held for about ten days, including several days before the ceremony and a week after it. Everything is for sale, but brassware is the most common item. People believe that buying things from the bazaar brings blessing to their homes. Fortune telling, athletic contests, and the performances of the religious passion play accompany the sales. On the day of the ceremony, tens of thousands of people gather to participate in or watch the ritual. The participants are exclusively men from the Fin area of Kashan, and no outsiders are allowed. During the ceremony, the participants gather in the court of the neighboring Imamzadeh. From there, they run to the mausoleum, brandishing their cudgels and shouting the name of Imam Hossein. After walking around the court of the mausoleum several times, they calm down, and a clergyman or any other important guest delivers a speech. After that, the Fin elders direct that the carpet should be removed from the crypt. The carpet can be any carpet from the mausoleum's collection, but it is meant to symbolize Sultan Ali's praying rug on which he was killed. The carpet is rolled up and wrapped in a black cloth. When people see the carpet, their agitation reaches its peak, and the shouting and brandishing of cudgels become extremely fierce. The Fin men take the carpet on their shoulders and carry it to the spring, where they sprinkle water on it to symbolically wash it. From there, the carpet is brought to the foot of a hill beside the mausoleum and then is returned to the crypt, only to be removed again the next year. The unceasing yelling and shouting, and the general atmosphere of mourning, are part of the ceremony. The ceremony is over shortly afternoon. The Friday of the week after the ceremony has a ritual of its own called Seven Imamzadehs. It is held by men wearing black, who beat their chests and recite mourning verses.

|

Sohrab Sepehri

Sohrab Sepehri, poet and painter, was born in 1928 in Kashan. After graduation from the Faculty of the Arts in Tehran University, he worked in several government agencies while on side pursued his personal interest in poetry and painting. During these years, he also traveled to Europe, the Far East, and Africa. His travels gave him a perspective on his mother's culture. In 1964, he resigned from governmental work and focused all his time and energy on poetry and painting. He lived in the USA for one year and in Paris for two years. During this period, he produced numerous expressionistic paintings, which captured many of the themes that recur in his poetry. In 1979, he was diagnosed with cancer and was treated in England. In 1980, he passed away in Tehran and was buried in the courtyard of Mashhad-e Ardehal. His legacy comprises a collection of poetry published in a single volume named Hasht Ketab ("Eight Books"), some prose, and an impressive assemblage of paintings.

- Details

- Category: Where to go in IRAN